From Stability to Productivity: The Structural Logic of Yield-Bearing Stablecoins

Introduction

In the evolution of any monetary system, liquidity and assethood always emerge in sequence.

Whether shells, metals, or paper currency, money originally served as a medium of exchange and a unit of account. Its “asset” property, the ability to accrue interest, appreciate in value, be allocated, and be managed, arose later as a byproduct of financial institutions, gradually forming once the circulation system matured.

In the modern financial system, after a long institutional evolution, these two attributes have reached a highly stable equilibrium.

Money has been seamlessly embedded into the yield structure at every stage of circulation: bank deposits accrue interest, money market funds, short-term Treasury bills, and repo mechanisms together form an invisible risk-free yield chain that allows money to generate income naturally while circulating.

By contrast, the on-chain monetary system remains in its early stage, where the realization of liquidity far outpaces the development of asset attributes.

Stablecoins enable value to circulate efficiently across decentralized networks, but this only fulfills the first layer of money’s function. They have yet to form a complete yield chain, nor can they reflect the time value of money at the system level.

In other words, the “on-chain dollar” has not yet become a financial asset in the true sense.

Yield-bearing stablecoins aim to address this gap by supplementing the asset dimension of on-chain money, allowing digital currency not only to transfer value but also to generate time value, thus guiding decentralized monetary systems toward a more complete financial form.

Accordingly, this paper will examine the subject from four perspectives:

Anchoring Structures – how stablecoins establish and maintain value correspondence with on-chain assets and real-world assets;

Yield Mechanisms – how returns are generated, measured, and transmitted within token systems;

Regulatory Framework and Its Evolution – how existing legal regimes define and constrain yield-bearing stablecoins, and how structural flexibility or institutional innovation may emerge through the interaction between regulatory consensus and market demand.

Attributes of Yield-bearing stablecoins

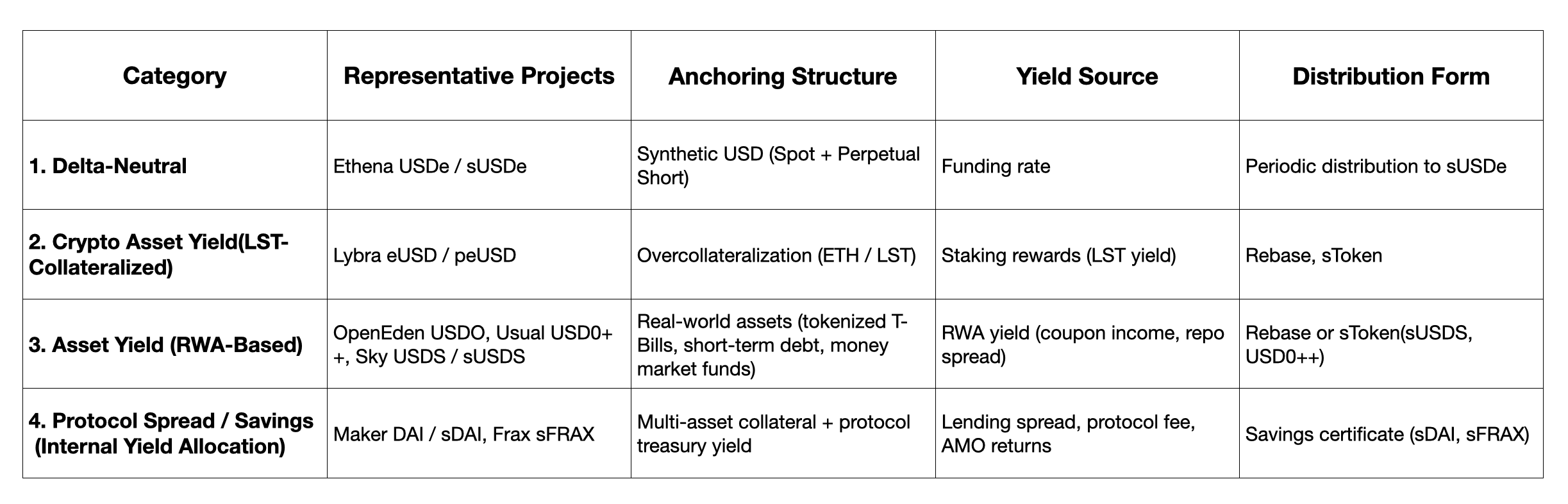

Yield-bearing stablecoins are not a single form but a series of on-chain financial experiments centered on “anchoring structures” and “yield distribution mechanisms.”

At the fundamental level, they all attempt to recreate an interest-bearing currency on-chain. The differences lie in three aspects:

1. Anchoring Structure (Backing / Collateral): where the funds originate and how stability is established;

2. Yield Source: from which side of the market the yield is derived, crypto collateral, derivative hedging, real-world assets, or internal protocol spreads;

3. Distribution Form: how users receive the yield-bearing asset.

The combination of these three dimensions forms the classification framework for all yield-bearing stablecoins currently on the market.

The evolution of stablecoins is not a simple transition “from non-yielding to yielding,” but a process of constructing relational linkages between stability and yield. Delta-Neutral models rely more heavily on derivatives markets; collateral-based models draw natural yield from staked crypto assets; RWA-based models directly incorporate real-world interest-bearing instruments; protocol spread models derive redistributable profits from within the system itself. Together, they form a new layered structure: the credibility of the anchor determines stability, the yield source determines sustainability, and the distribution form determines compliance and transmissibility.In the following sections, we analyze the similarities and differences among these stablecoins across these dimensions, and further explore their respective compliance pathways and developmental trajectories.

Classification of Anchoring Structures: Value Anchors and Structural Anchors

In the on-chain monetary system, stability is not granted by external declaration but maintained through the internal coherence of asset–liability structures. The “anchor” of a stablecoin, in essence, refers to how the system ensures that the purchasing power of each token unit does not erode with market fluctuations. Mechanistically, stablecoins today can be categorized into two fundamentally different anchoring models: value anchors and structural anchors.

1. Value Anchors

A value anchor is based on assets that are measurable and redeemable. Each stablecoin corresponds to verifiable collateral, which can consist of either on-chain assets or real-world assets. Through mechanisms such as collateralization, liquidation, reserves, or custody, the system ensures that each issued stablecoin can be redeemed at par value for its backing asset at any time. The key to a value anchor lies in the asset coverage ratio and the reliability of the redemption mechanism.

In the crypto context, value anchors can be divided into two typess:

On-chain collateralized value anchors: exemplified by MakerDAO’s DAI, which is overcollateralized with ETH or other stablecoins;

Real-world asset (RWA) value anchors: such as USDC, USDO, or frxUSD, backed 1:1 by cash, Treasury bills, or money market funds.

This anchoring method provides the strongest form of certainty. It allows the stablecoin’s value to be fully traceable to a concrete balance sheet, where the essence of stability is “asset value ≥ liability value,” with risk concentrated on custody and liquidity.

2. Structural Anchors

The core of a structural anchor does not lie in the static value of assets but in the dynamic balance of positions or model structures. By controlling exposure, the system maintains approximate stability in USD terms at the aggregate level. A representative example is Ethena’s USDe, whose asset side consists of mutually offsetting positions:

spot holdings (such as ETH or stETH) paired with short perpetual contracts form a delta-neutral structure. Spot yields and short funding rates offset each other, allowing the system’s net asset value to remain stable amid price volatility.

The stability of a structural anchor depends on the depth and continuity of market structure, as long as derivatives markets maintain sufficient liquidity, the hedging relationship can be sustained over time.

A structural anchor is inherently dynamic. In a broader framework, it can be described as a multi-asset, multi-derivative neutral system. Through systematic asset allocation and risk distribution, the overall asset pool maintains balance across macro risk dimensions. Assets may span both crypto and real-world markets, covering short- and long-term debt, various yield curves, volatility ranges, and geographic exposures. The system does not seek price anchoring to any single asset but aims for factor neutrality across the entire portfolio.

3. Interrelation of Value and Structural Anchors

Value anchors and structural anchors together constitute two distinct logics of stability within on-chain monetary systems. The former is anchored by substance, securing redemption through static value; the latter is anchored by structure, maintaining net value through dynamic balance. In financial analogy, value anchors correspond to the bank reserve system,

while structural anchors resemble market-neutral funds. They are not substitutes but represent two ends of an evolutionary path, from static trust to structural trust, within the broader architecture of stablecoin systems.

Yield Source Mechanisms

The core of yield-bearing stablecoins lies in the asset sides’ ability to generate sustainable revenue. Their yield originates from the operating income or financial returns of real assets, distinguished from liquidity mining or other token-based incentives. Such yield does not depend on token supply design or secondary market price mechanisms.Instead, it is supported by verifiable cash flows derived from staking rewards, funding rate spreads, bond coupons, or protocol-level capital utilization—representing measurable output achieved while maintaining the anchoring structure.

From on-chain practices, the yield sources of stablecoins can be broadly divided into four categories: collateral asset yield, derivative hedging yield, internal protocol spread, and real-world asset (RWA) coupon income.

(1) Collateral Asset Yield

This type of yield comes from the inherent earning capability of the collateralized asset itself, the most direct and natural form of income. A typical example is the stablecoin backed by LSTs (Liquid Staking Tokens), such as Lybra’s eUSD. The collateral assets continuously produce yield through staking or validation activities, and the protocol allocates part of this yield to stablecoin holders, forming a “holding-generates-yield” structure. Such income is stable and predictable in nature.

(2) Derivative Hedging Yield

Hedging-type stablecoins derive yield from market structure yield in derivatives markets, mainly through funding rates. In markets with a long-side bias, short holders continuously receive funding payments, which constitute the protocol’s natural cash flow. In more complex structures, additional yield may arise from cross-market spreads or term-basis differences between contracts of different maturities. The stability of this income depends on market liquidity and volatility structure, with long-term sustainability determined by the depth of derivatives markets.

(3) Internal Protocol Spread

This yield source does not originate directly from collateral assets or market positions but from internal capital allocation mechanisms within the protocol. Typical examples include MakerDAO’s sDAI and Sky’s sUSDS, where the protocol sets interest rate differentials across pools and redistributes system surpluses to savings-token holders through liquidation penalties, borrowing spreads, stability fees, or treasury reinvestments.This represents a form of internalized yield, whose magnitude depends on the protocol’s overall risk management efficiency and the effectiveness of its asset–liability structure.

It links yield generation with governance, granting the system attributes similar to a quasi–money market fund.

(4) Real-World Asset Yield

When a stablecoin is backed by tokenized T-Bills, short-term debt instruments, or money market funds, its yield comes directly from real-world interest income.Representative examples include OpenEden’s USDO and Usual’s USD0++. The system holds actual bonds or repo agreements and generates stable annualized returns through coupon payments or repo spreads. The advantage of RWA-based yields lies in their predictability and transparency, though they are subject to stricter compliance constraints—particularly in North America and the EU, where yield distribution may cross into the domain of securities regulation, requiring independent legal and structural separation.

Collectively, these yield channels form the structural landscape of yield-bearing stablecoins. Collateral asset yield and RWA coupon income constitute passive yields, while derivative hedging yield and internal protocol spread represent structural yields. The former rely on the asset properties of value anchors,whereas the latter emerge from the operational mechanisms of structural anchors.

Yield Distribution Forms

The distribution mechanism of yield-bearing stablecoins determines how yield is represented and transmitted within the system.

The most common models include:

(1) Rebase — balances are periodically adjusted upward with each yield cycle, increasing token quantity while maintaining a constant unit price. This model is often adopted by protocols that position yield as a primary feature, such as eUSD and USDO.

(2) Tokenized Certificate (sToken / Vault) — the base stablecoin itself does not accrue yield; holders must stake or convert it into a yield-bearing certificate to receive returns, as seen in sDAI and sUSDS.

(3) Internal Accumulation — yield is not distributed directly but instead retained within the system’s asset base to strengthen reserves or fund buybacks, as in certain RWA- or treasury-strategy-based stablecoins.

These distribution forms do not alter the underlying sources of yield, but they do affect how the system is perceived in terms of regulation, accounting treatment, and user experience.

Regulatory Framework and Evolution

The regulatory issue surrounding yield-bearing stablecoins lies in the fact that the presence of yield changes their legal identity. Once a stablecoin is capable of generating and distributing yield to its holders, it inevitably enters the intersection between currency and securities. The key concern for regulators is not the level of yield, but its source, distribution path, and risk-bearing structure.

The divergence in regulation stems from the logic of classification:

whether to regard a yield-bearing stablecoin as an extension of money or as a variant of investment products.Across jurisdictions, the supervision of interest-bearing stablecoins remains highly stringent.

The determining standard among jurisdictions does not depend on whether the yield is “naturally generated,” but on whether the yield is distributed, expected, and continuous. For instance, even though USYC produces yield naturally and maintains full redemption capability, its legal classification under compliant frameworks is that of a tokenized money market fund. In most existing regulatory regimes, issuing a stablecoin that distributes yield directly to the public is explicitly prohibited.

Extending from the previously discussed structure of yield-bearing stablecoins, a stablecoin system can be divided into three layers: anchoring, revenue generation, and distribution.

The anchoring layer ensures stability and redemption; the revenue layer represents the asset-side mechanism that generates cash flow and determines system sustainability; the distribution layer determines how yield is transmitted among holders. In yield-bearing stablecoins, these layers are increasingly being institutionally differentiated.

Following the historical trajectory of monetary development, the future direction of stablecoin regulation may take the form of layered supervision, though a more accurate description would be a refinement and separation of responsibilities. In yield-bearing stablecoins, stability and yield are often internally connected. Taking USDe as an example, both its stability mechanism and yield originate from short positions. They stem from the same asset structure yet correspond to different risks and responsibilities:

the neutral risk management of the short exposure relates to the stability responsibility of the anchor,while the funding-rate-derived yield constitutes operational responsibility.

Regulation can delineate boundaries of accountability along this logic, ensuring that risk management remains traceable and properly attributed.

Such separation does not alter the integrity of the structure; it merely clarifies the ownership of risk at the institutional level, preserving the supervisory function without constraining innovation.

Epilogue

The future of stablecoins will unfold in a landscape of diversification. Across multiple dimensions, anchoring structures, yield generation, and regulatory adaptation—different models will coexist:

some prioritizing asset security, others emphasizing structural efficiency, and still others exploring the equilibrium between yield and stability. Together, they form a broader monetary laboratory in which stablecoins are no longer products of a single institutional logic, but outcomes of continuous interplay between structural innovation and regulatory constraint.

These innovations, in essence, redefine what “stability” means. For some, stability lies in the certainty of reserves and redemption; for others, it emerges from structural self-balance and market neutrality. Such new forms are prompting regulatory systems to reassess the very boundaries of money itself. The goal of compliance should therefore evolve to include the recognition of structure and accountability.

The stablecoin systems of the future may no longer pursue a unified global standard. Instead, they are likely to evolve into a multi-layered, regionally differentiated, and functionally specialized ecosystem, where various types of stablecoins find their own viable space within distinct jurisdictions and regulatory paradigms.

Media

Ideas & Inspiration

Polymarket---The On-Chain Prediction Market Pricing the Future

OOKC Insight | USDe Didn’t Actually “Depeg”

LADT Launch | OOKC Drives Digital Economy Growth